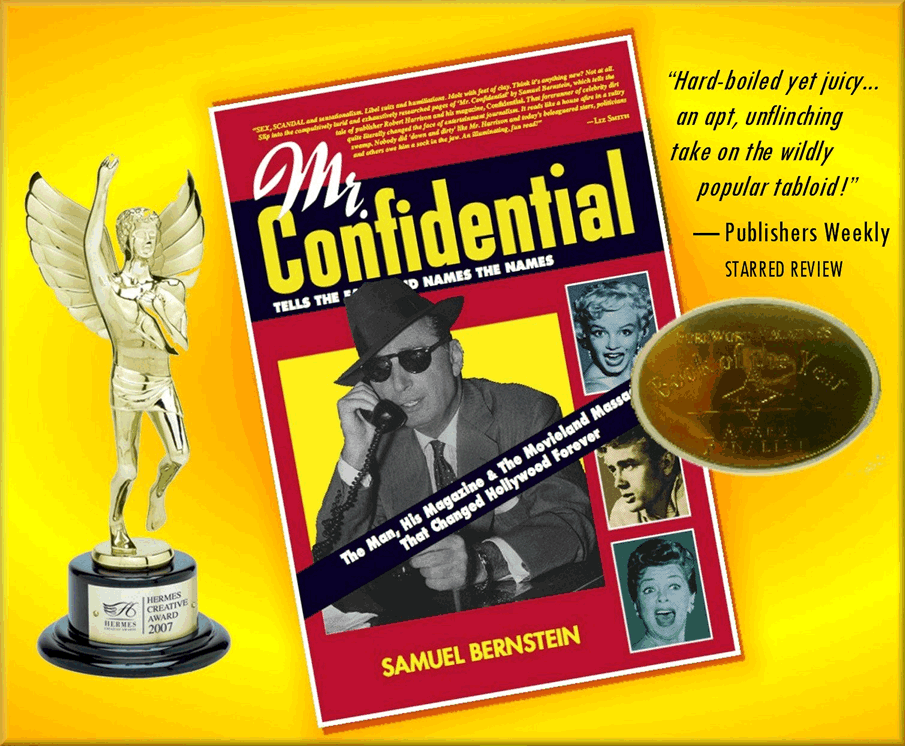

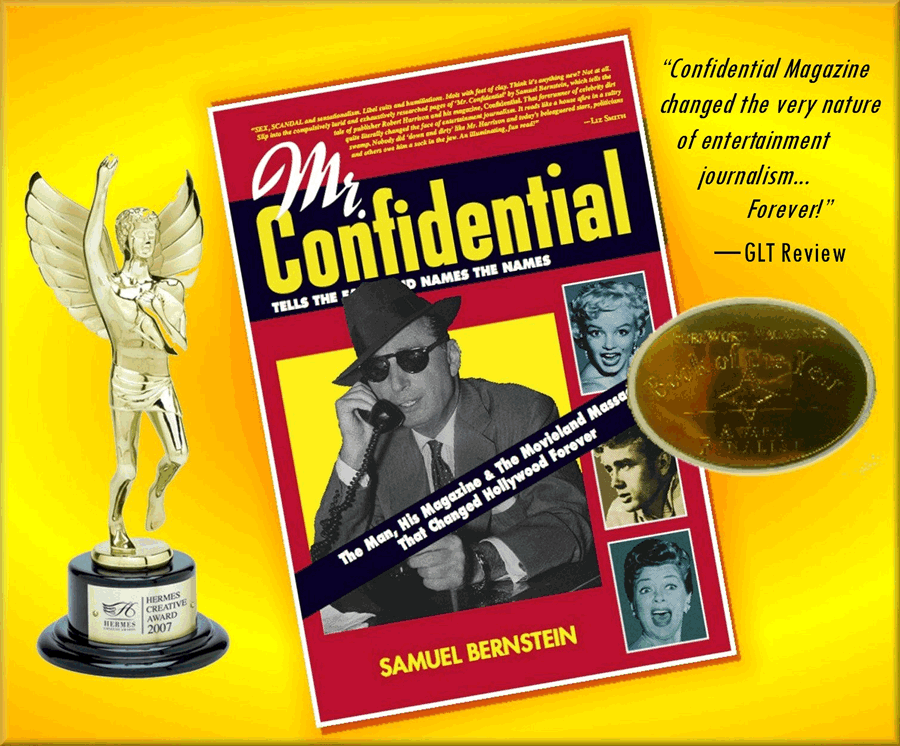

| Liz Smith says Mr. Confidential reads like, "A house afire in a sultry swamp!" Publishers Weekly gives it a starred review, and calls it, "Hard boiled-yet juicy... an apt, unflinching take on the wildly popular tabloid!" And Booklist raves, happily urging readers to, "Get a load of it!" while Cox News Service goes highbrow, chapioning the book's take on, "The neurotic underpinning of the American Dream." But sshhh! Keep it Confidential... | |||||

|

|||||

|

|

| SCOTT EYMAN, COX NEWS SERVICE For a brief five years, "Confidential" was the hottest magazine in the world. From a standing start in 1952, it was selling 5 million copies an issue in the mid-'50s, until its creator and editor, Robert Harrison, bailed out in 1958. "Confidential" succeeded by writing semi-scandalous stories about celebrities that tended to be true, mixed with trendy anti-communism that tended to be false. Another staple was miscegenation; "Confidential" was always running stories about the cross-racial sexual exploits of Sammy Davis Jr., Billy Daniels, Dorothy Dandridge or Marlon Brando. Today, it can be seen that the magazine lived off a working-class distrust of crazy Hollywood types and their lefty friends that still thrives in the environs of Fox News. Like Spy in the '80s, it was the right magazine at the right time. It constituted a busting loose from the movie studios' rigid control over information that had held sway since the 1920s. Nobody knew that Spencer Tracy was a drunkard or that Marlene Dietrich liked women as well as men, because the studios controlled access. Beyond that, there was the question of the advertising spigot that could be shut off at a moment's notice if any journalist got a little too frisky. But "Confidential" was a feisty independent, and its advertising was generally low-end; it made it on circulation alone, which is why the layout was a lurid mix in screaming reds and yellows. "Confidential" didn't call Liberace a homosexual, exactly; it just headlined its story, "Why Liberace's Theme Song Should be `Mad About the Boy!'" Among those the magazine outed were Van Johnson, Walter Chrysler Jr., under-secretary of state Sumner Welles, Tab Hunter and Johnny Ray. Likewise, the actress Lizabeth Scott wasn't called a lesbian; she was a "baritone babe," a fabulous locution that Walter Winchell might have envied. Harrison's sources were bartenders, governesses, mistresses and the occasional professional such as Barbara Payton, who starred with James Cagney and Gregory Peck, and who ended up as a $10 hooker. The movie studios couldn't control the magazine, so they had to learn to play a new game. When "Confidential" was planning on outing Rock Hudson, his agent gave up the juvenile prison record of Rory Calhoun, also a client but a much less important star. Hudson's career was, for the moment, safe. Bernstein adopts an oddly benign view of the damage the magazine wrought, however, probably because his sources were Robert Harrison's relatives, who were mostly supported by him. Harrison, in Bernstein's telling, was a bumptious huckster with the soul of a racetrack tout who loved blondes and good times. "It so happens I have three white polo coats," he said. "I love them. What the hell's wrong with that? Any guy with a little showmanship would go for it." Oddly, Harrison never married, but then, he never had another success like "Confidential" either. People in the '50s enjoyed believing in Rita Hayworth's skills as a mother, in June Allyson's wholesomeness, in Rock Hudson's heterosexual virility. It is entirely possible to lose oneself in the fantasy of idealized belief while still knowing deep down that the essential truth of that belief is about as sturdy as Jell-O. Bernstein's book contains a lot of information, and it also does the inestimable service of reprinting every cover of "Confidential" and a generous sampling of the stories themselves. Together, they provide a window into an alternate view of a supposedly tranquil time – the neurotic underpinnings of the American dream. |

LIZ SMITH:

|||